Minocycline-induced discoloration of the alveolar bone: A case report

Article information

Abstract

Minocycline, a broad-spectrum tetracycline antibiotic, is known to cause tissue pigmentation, although involvement of alveolar bone is rare and often underrecognized. This report describes a case of blue-gray alveolar bone pigmentation discovered incidentally during extraction of bilaterally impacted mandibular third molars in a 17-year-old male. The patient had a history of prolonged minocycline use following orthopedic surgery. Despite the pigmentation, the affected bone demonstrated normal density and structure, and postoperative healing was uneventful. Although histopathologic confirmation was not pursued, the patient’s medical history and clinical presentation were consistent with minocycline-induced pigmentation. Awareness of this uncommon condition is essential to prevent misdiagnosis, avoid unnecessary intervention, and reassure patients. Current evidence suggests that such pigmentation does not adversely affect bone quality or healing capacity. This case highlights the importance of recognizing minocycline-induced bone pigmentation to prevent misdiagnosis and unnecessary intervention.

Introduction

During surgical procedures, the incidental discovery of pigmented bone can raise concerns for the surgeon regarding the potential pathological state of the bone and its impact on the healing process. The causes of bone discoloration are varied, and minocycline is one potential, though uncommon, etiology. While tetracycline-related dental discoloration is well known to dental professionals, minocycline-induced bone pigmentation is a much rarer phenomenon, and many clinicians are unfamiliar with its occurrence. Additionally, the precise nature of minocycline-induced bone pigmentation is not fully understood.

Minocycline is a commonly prescribed tetracycline antibiotic used for the treatment of acne vulgaris, rosacea, and various chronic infections [1,2]. While it is generally well tolerated, minocycline is known to cause a variety of side effects, including tissue pigmentation [3]. This pigmentation can affect multiple tissues, including the skin, sclera, nails, thyroid, and bone [2,4,5]. Among these, minocycline-induced alveolar bone pigmentation is rare and often discovered incidentally during dental procedures.

This report presents the case of a 17-year-old male who visited our clinic for the extraction of bilateral impacted mandibular third molars. During the surgical procedure, incidental blue-gray pigmentation of the alveolar bone was observed. This report aims to highlight clinical presentation and discuss the underlying pathophysiology, differential diagnosis, and management strategies of minocycline-induced alveolar bone discoloration.

Case Report

A 17-year-old male visited our clinic for the extraction of bilaterally impacted mandibular third molars. He had a history of a car accident approximately 16 months prior and had been under treatment at the orthopedic surgery department since that time. The patient was otherwise in good general health.

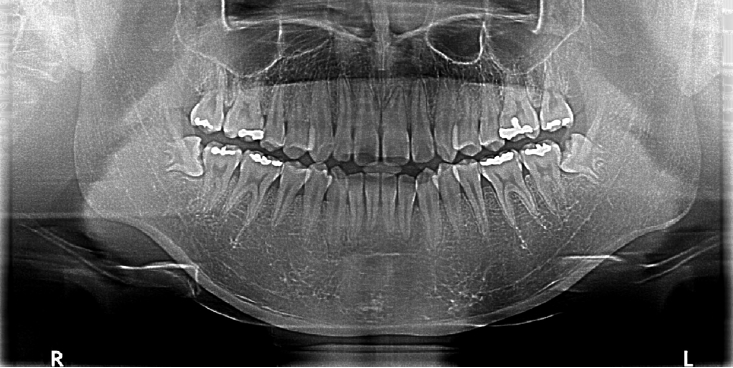

Intraoral examination revealed no significant abnormalities. Panoramic radiography showed impacted mandibular third molars (#38 and #48) bilaterally as shown in (Fig. 1).

Preoperative panoramic radiograph showing bilaterally impacted mandibular third molars without apparent bony pathology.

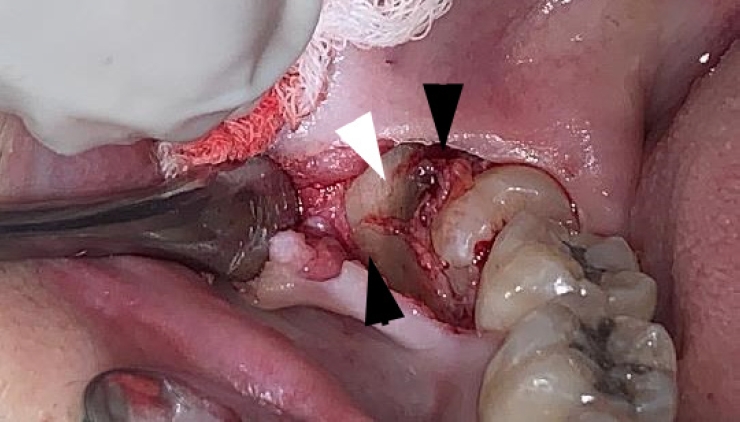

Intraoperatively, alternating bands of blue-gray and yellow discoloration of the alveolar bone was noted around both #38 and #48. (Fig. 2 and 3) No discoloration of adjacent teeth was observed. The overlying mucosa showed no discoloration or textural changes. During alveolar bone reduction, the bone density and quality appeared normal, and no other abnormal signs or symptoms were present.

Alternating bands of blue-gray and yellow discoloration of the alveolar bone observed during flap reflection for surgical extraction of the left mandibular impacted third molar.

Alternating bands of blue-gray and yellow discoloration of the alveolar bone observed during flap reflection for surgical extraction of the right mandibular impacted third molar.

The patient had been receiving long-term care from the orthopedic surgery (OS) department, so his medical records were reviewed. Sixteen months earlier, he had sustained a right tibia and fibula fracture with associated skin necrosis. He underwent multiple surgical interventions, including open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), skin grafting, and wound debridement. Pus culture obtained during that time revealed Staphylococcus aureus, which was sensitive to tetracycline. Minocycline was prescribed accordingly by the orthopedic team: 400 mg/day for one week, followed by 200 mg/day for five months, and subsequently 400 mg/day for approximately six months.

At the follow-up visit for suture removal, the extraction sites showed normal healing, and the patient reported no symptoms or complications (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Minocycline is a broad-spectrum antibiotic of the tetracycline class, commonly employed in the management of acne vulgaris, rosacea, and various chronic infections, as well as an adjunctive treatment in rheumatoid arthritis [1,2]. Minocycline exhibits superior antimicrobial efficacy compared to other tetracyclines and reaches peak serum concentrations within a few hours post-administration [5]. Additionally, beyond its antimicrobial activity, minocycline possesses anti-inflammatory effects, including the reduction of chemotaxis, suppression of collagenase activity, and downregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines. These actions contribute to its therapeutic effectiveness in various inflammatory conditions [5-8]. These actions contribute to its therapeutic effectiveness in inflammatory conditions [6,9].

Hyperpigmentation is considered a rare, yet well-established adverse effect of minocycline therapy [3]. Minocycline-induced pigmentation has been documented in various tissues, including the skin, teeth, nail beds, bones, thyroid, oral mucosa, sclera, and heart valves [2,4,5].

Cutaneous pigmentation resulting from minocycline has been widely reported, with four distinct types described in the literature [4]. Type I presents as blue-black macules at sites of previous inflammation and scarring, such as facial acne scars, due to dermal deposition of pigmented granules likely iron chelates of minocycline; Type II appears as blue-grey discoloration on previously healthy skin, often on the shins and forearms, linked to the deposition of minocycline metabolites; Type III is characterized by a muddy-brown discoloration in sun-exposed areas, typically the face, resulting from increased melanization of the skin's basal cell layer and elevated melanin in epidermal and dermal macrophages; and Type IV shares the same etiology as Type III but is exclusively found in preexisting scars, not limited to sun-exposed areas. The etiology of minocycline-induced skin pigmentation is believed to be associated with the deposition of iron in dermal macrophages [6,10]. This process is thought to be linked to the degradation products of minocycline or the lysosomal oxidation products formed when minocycline chelates iron. The differential diagnosis encompasses a range of conditions, including melasma, pigmented contact dermatitis, drug-induced hyperpigmentation, Addison's disease, hyperthyroidism, hemochromatosis, and cutaneous malignancies. These conditions are typically characterized by either an increase in melanin production, an elevation in melanocyte density, or the deposition of other substances contributing to skin discoloration [11]. Management of minocycline-induced soft tissue pigmentation generally involves cessation of the antimicrobial agent or laser therapy [12,13]. Nevertheless, residual pigmentation may persist despite these interventions, highlighting the potential for long-term tissue discoloration [3,11,13]. In a pilot study by Bowles et al, it was suggested that vitamin C supplementation could prevent minocycline-induced pigmentation. The authors recommended that clinicians advise patients taking minocycline to increase their vitamin C intake [14].

The presence of pigmentation in the oral soft tissues typically manifests as a distinct blue-gray or brown hue, which is predominantly attributed to the visibility of pigmented bone through the thin overlying mucosa, rather than direct involvement of the soft tissues themselves [4-6,15-18]. In contrast, instances of genuine oral soft-tissue pigmentation are exceedingly rare, and when present, they have been documented primarily in the tongue, lips, buccal mucosa, and gingiva [18]. The differential diagnosis for minocycline-induced pigmentation of the alveolar bone includes conditions such as malignant melanoma, Kaposi’s sarcoma, amalgam and non-amalgam tattoos, melanotic macules, smoker’s melanosis, melanotic nevus, oral melanoacanthoma, heavy metal poisoning, racial pigmentation, Addison’s disease, hemochromatosis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, McCune-Albright syndrome, neurofibromatosis, and other drug-induced pigmentations [6,15]. Notably, most of these conditions involve predominantly soft tissue pathologies, unlike the hard tissue involvement characteristic of minocycline-induced pigmentation. This is likely attributable to the anatomical characteristics of the oral environment, where the overlying mucosa is thin and tightly adherent to the underlying bone, making it difficult to determine whether the discoloration originates from the soft tissue itself or the subjacent hard tissue.

Bone discoloration due to minocycline has been reported in orthopedic practice. The affected bone typically appears black or gray in color, leading to the descriptive term 'minocycline-induced black bone disease’. The minimum dosage and duration necessary for minocycline-induced bone discoloration, and their association with the extent of bone staining, remain unclear [15,19]. It is hypothesized that the degradation of minocycline's aromatic ring leads to the formation of insoluble black quinone, which may contribute to the bone pigmentation [9]. Differential diagnoses for bone discoloration include ochronosis, metabolic bone diseases, heavy metal deposition (e.g., titanium, iron, copper), hemophilic arthropathy, metastases, long-term minocycline use, infection, avascular necrosis, and bone inflammation [20]. Some reports have employed fluorescence to identify minocycline-pigmented bone [8,21]. However, at physiologic pH, while tetracycline-stained bone fluoresces yellow under ultraviolet (UV) light, minocycline-stained bone does not exhibit fluorescence. Minocycline is unique among tetracyclines in that it fluoresces only in acidic environments. Therefore, UV fluorescence may not be a reliable diagnostic indicator for minocycline-related bone discoloration [6,15,19,22]. In terms of pigmentation depth, Friedl et al. [23] removed alveolar exostoses and observed significant discoloration after osteoplasty extending to a depth of 3–4 mm. However, there is limited information in the literature regarding the extent of minocycline-induced staining within bone. Currently, there is no known method to selectively remove minocycline from pigmented bone. The duration of discoloration following the cessation of minocycline therapy remains unclear and may be irreversible. While this may vary by the tissue type, discoloration of bone and teeth appears to be permanent [5,9,15,17]. The prevalence of minocycline-induced bone pigmentation, as well as its potential long-term adverse effects on human bone, remains to be established [8]. There has been a report that tetracycline-treated bone remains structurally sound and can be effectively utilized in grafting procedures [15]. Additionally, there are claims suggesting a possible association between tetracycline-induced staining and enamel hypoplasia resulting from high doses of tetracycline during the calcification process [22]. Rashid et al. suggested that minocycline-induced bone discoloration (MIBBD) could serve as a marker of metabolically active bone. They supported this idea by highlighting the ability of tetracyclines to be incorporated into healthy bone and fluoresce under ultraviolet light, a characteristic used to identify viable bone during surgical debridement in chronic osteomyelitis cases [20,24,25]. To date, there are no documented cases of pathological alterations in adult bone associated with minocycline use [19,26]. Westbury and Najera reported that no specific treatment is required, as the condition appears to be clinically benign [15]. Furthermore, Oklund et al. demonstrated that bone affected by minocycline-induced pigmentation retains normal structural integrity [15,27,28]. Multiple studies have corroborated that, in adult patients, hyperpigmentation does not adversely impact bone quality or compromise its biomechanical properties. Importantly, there is no evidence to suggest impaired bone healing, and surgical interventions can be undertaken without increased risk [5,27,29,30]. Reports regarding the effects of tetracyclines on bone remain inconsistent. As previously mentioned, Rashid et al. proposed that bone with tetracycline deposition may serve as a marker of viable, metabolically active bone, based on its ability to fluoresce under ultraviolet light and the known affinity of tetracyclines for incorporation into healthy bone tissue [20]. Problems associated with tetracyclines have been observed in relation to growing bone [21]. Studies indicate that tetracyclines cause a reversible decrease in fibular growth in premature infants [6,23,31]. Animal studies have also shown a reduction in bone maturation in developing monkeys and an inhibition of mineralization and development in chick embryos [5]. However, no harmful effects were noted in adult rats, dogs, or monkeys, suggesting that the impact on bone development is more pronounced during growth stages [5,32]. Animal studies on minocycline have demonstrated a decreased resorption of bone, without adverse effects on bone growth [8]. These studies have shown a dose-dependent inhibition of osseous resorption following minocycline treatment [33]. In ovariectomized rat models, which simulate osteoporosis, treatment with minocycline over eight weeks resulted in moderate increases in bone mineral density, accompanied by notable changes in the microanatomy of trabecular bone [34]. Additionally, there are reports indicating that minocycline may reduce alveolar bone loss in rats with periodontitis and promote bone formation while decreasing bone loss in ovariectomized aged rats1, [35]. Udagawa et al. reported that minocycline inhibits osteoclast differentiation [36]. Importantly, there have been no reports suggesting that long-term exposure to minocycline leads to structural compromise in adult human bone [21]. Some practitioners have even reported successful outcomes in procedures involving minocycline-induced pigmented bones, further supporting its safety in certain clinical contexts [21]. A review of the literature revealed no reported cases in which treatment was undertaken specifically for minocycline-induced pigmentation of bone, suggesting that clinical intervention is not typically warranted.

In summary, minocycline-related soft tissue pigmentation manifests in four types, some of which may resolve after discontinuation. Laser therapy has been explored as a possible intervention, and research suggests that coadministration of Vitamin C may help prevent the development of pigmentation [37]. Pigmentation in the oral mucosa is most often a result of the alveolar bone's pigmentation showing through. The minocycline-induced bone pigmentation does not consistently show diagnostic characteristics under UV light, and its depth remains undetermined. Furthermore, removing this pigmentation is challenging. However, it is generally reported that minocycline does not have a negative impact on bone morphology or quality. In fact, many studies suggest that minocycline may increase bone density.

This case report presents an instance of alveolar bone discoloration likely caused by prolonged minocycline therapy. Although the patient was not receiving minocycline for common indications such as acne or arthritis, he had been prescribed the antibiotic after a pus culture identified Staphylococcus aureus sensitive to tetracyclines.

Histopathological analysis was not performed in this case, as removal of alveolar bone was not necessary for the extraction procedure and would have resulted in unnecessary harm to the patient. The extraction sites healed without complications.

While dental professionals are generally well aware of tetracycline-induced pigmentation of teeth, minocycline-associated pigmentation of alveolar bone is much less frequently encountered. This is particularly challenging when no pigmentation is observed in the overlying mucosa or dentition, and radiographic imaging yields no specific findings, potentially leading to perplexity for surgeons during the unexpected intraoperative discovery of pigmented bone.

This case serves as a reminder of this rare but important clinical finding. When unusual bone discoloration is observed, and if biopsy is feasible or clinical concerns are present, histological evaluation should be considered. However, if the patient’s medical history strongly suggests minocycline-induced pigmentation and there are no other signs of pathology, careful observation may be an appropriate and sufficient course of action.

Awareness of minocycline-induced bone pigmentation can help avoid unnecessary interventions and ease patient concerns. Affected bone appears to maintain normal biological integrity and healing capacity. If future cases show impaired healing in the context of such pigmentation, reporting these findings may offer meaningful insights for surgical decision-making.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

None