| J Korean Dent Assoc > Volume 63(1); 2025 > Article |

|

Abstract

A patient who underwent sinus floor augmentation (SFA) for dental implants at a local clinic was referred to our dental hospital for the treatment of maxillary sinusitis and oroantral fistula. After successfully treating them, a second SFA was performed by an experienced surgeon without any intraoperative complications. However, during postoperative follow-up, the patient developed severe maxillary sinusitis again and was referred to the Department of Otolaryngology for endoscopic sinus surgery under general anesthesia. During the preoperative assessment, routine laboratory testing revealed that the patient was positive for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), a fact previously unknown to the healthcare providers. This case report discusses the increased risk of postoperative infection in HIV-infected patients and underscores the necessity of comprehensive pre-treatment evaluations for underlying health conditions in outpatient-based dental clinics. Additionally, a review of relevant literature is included to support these findings.

Sinus floor augmentation (SFA) is a well-established and reliable surgical procedure commonly used for the placement of dental implants in the posterior edentulous maxilla [1,2]. Although SFA can lead to several complications, such as wound infection, graft loss, and maxillary sinusitis, the incidence of sinusitis remains relatively low at approximately 4%, according to literature [1,2]. Despite Schneiderian membrane perforation or smoking history increasing the risk of maxillary sinusitis after SFA, the overall occurrence remains low [1,3].

Dental surgery is not an absolute contraindication for patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), but surgical site infections (SSIs) occur more frequently, especially in untreated HIV-infected patients [4,5]. If an HIV-infected individual is unaware of their status or conceals it from healthcare providers, the risk of postoperative complications is significantly elevated. Furthermore, such individuals may pose a potential risk of cross-infection to healthcare providers and other patients [5-7].

This case report explores the repeated occurrence of maxillary sinusitis following SFA in an HIV-infected patient who had not disclosed their HIV status to healthcare providers. The report discusses the increased risk of postoperative infection associated with HIV and emphasizes the need for comprehensive pre-treatment evaluations in outpatient-based dental clinics.

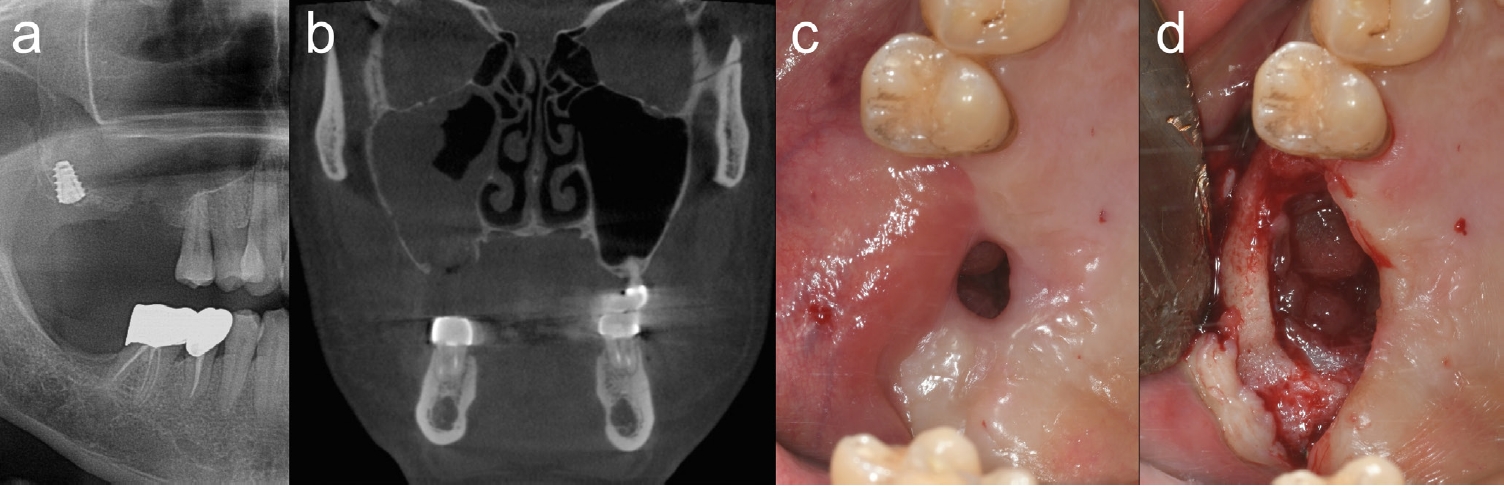

A 46-year-old male patient presented to our hospital after an unsuccessful attempt at dental implant placement and sinus floor perforation in the right maxilla at a private dental clinic. The patient reported a history of smoking but denied any other medical conditions. Clinical and radiographic examinations revealed maxillary sinusitis nearly filling the entire right maxillary sinus, along with a mal-positioned dental implant and a large perforation of the sinus floor (Figs. 1a-c). The patient underwent medication therapy, removal of the implant, debridement of inflamed sinus tissue, and closure of the oroantral fistula (Fig. 1d). Although a small residual fistula persisted, it healed favorably with conservative management.

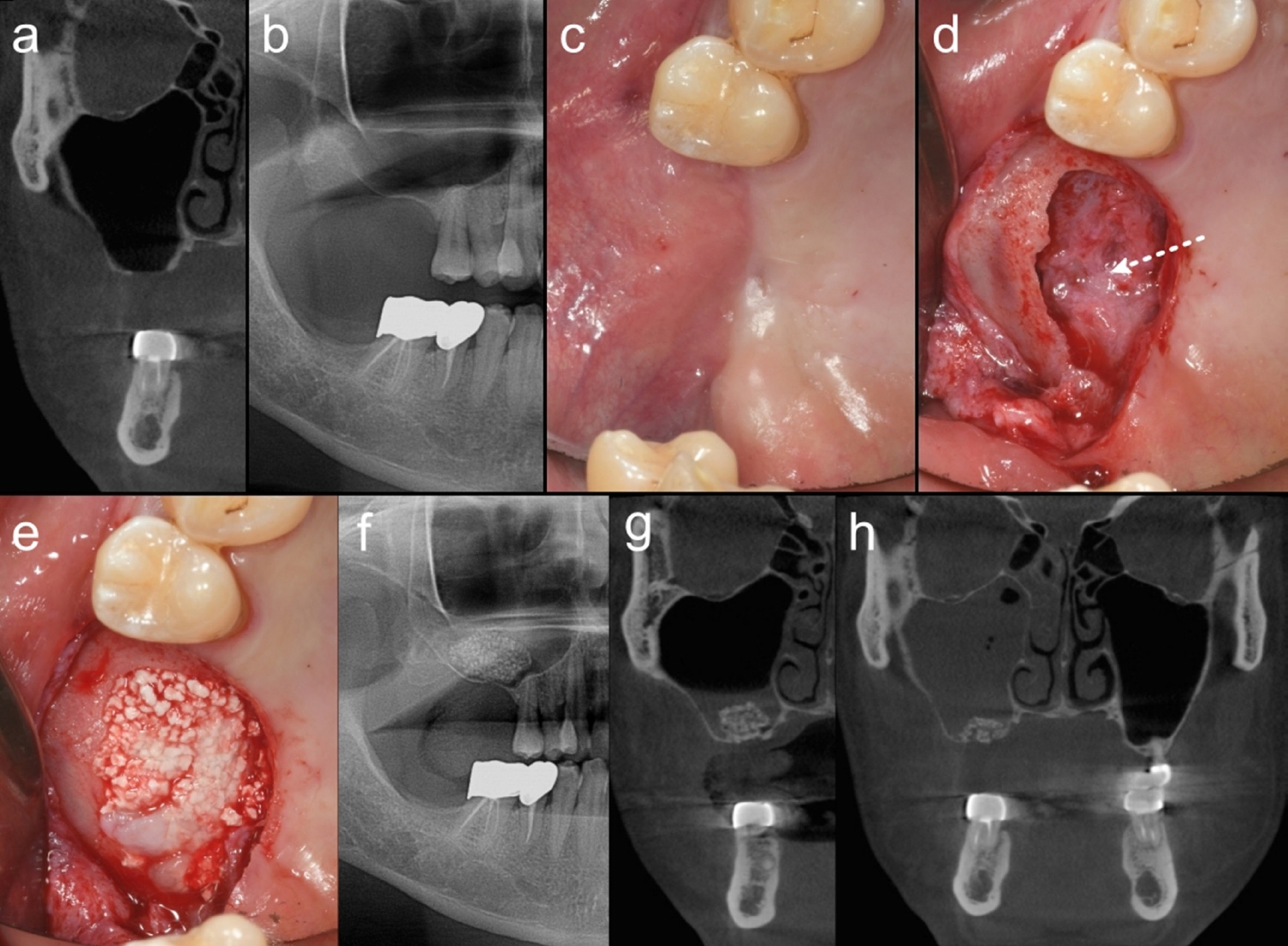

Approximately two months later, the patient returned, complaining of a foul, pus-like odor in his mouth. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed the right maxillary sinus completely filled with inflamed tissue. As there was no dental origin, the patient was advised to seek treatment at an otolaryngology (ENT) department, though the specific institution was not identified. Three months later, the patient returned to our hospital, and follow-up CT imaging showed a clear right maxillary sinus (Figs. 2d-g). The oral mucosa was completely healed without any residual fistula (Fig. 2c). SFA was y performed by an expert using bone morphogenetic protein-2 combined with hydroxyapatite and fibrin sealant carriers [8]. The procedure utilized the extensively perforated site of the right sinus floor without additional ostectomy, and no tearing of the sinus mucosa was observed during surgery (Figs. 1a-c).

At the one-month postoperative follow-up after SFA, the patient again complained of a recurrent foul odor. A CT scan revealed widespread maxillary sinusitis in the right sinus (Fig. 2h). Conservative treatments, including medication and nasal irrigation, were not effective, and the patient was referred to the ENT department within our institution. During preoperative evaluations for endoscopic sinus surgery, the ENT team discovered that the patient was positive for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The ENT department informed us of this diagnosis, which the patient had not previously disclosed. It remains unclear whether the patient was aware of his HIV infection and chose not to disclose it or was unaware of his condition. Following the diagnosis, the patient was referred to the department of Infectious Diseases for further management. He did not return for additional dental follow-up.

This case report presents a patient who was initially believed to be healthy, without a significant medical history aside from smoking history, but who experienced repeated maxillary sinusitis after dental implant-related procedures. The patient was later diagnosed with AIDS during preoperative laboratory examination for general anesthesia. This report aims to explore the impact of HIV infection on recurrent maxillary sinusitis and emphasize the importance of preoperative evaluations in dental outpatient settings, which have not traditionally been considered essential.

AIDS represents the advanced stage of HIV infection, where the virus weakens the immune system by targeting CD4+ T cells, reducing the body's ability to fight off infections and cancers. Without appropriate treatment, HIV progresses to AIDS, which is marked by severe immune compromise, leading to opportunistic infections and other AIDS-defining illnesses [9]. HIV-infected individuals are more susceptible to inflammation due to persistent immune activation, which remains present even with effective antiretroviral therapy. This chronic inflammation is driven by factors such as intestinal microbial translocation, depletion of regulatory T cells, and the presence of ŌĆśinflammagingŌĆÖ, which is a chronic, sterile, and low-grade inflammation associated with aging. These factors collectively lead to an increased risk of inflammatory conditions, such as sinusitis [10,11].

Furthermore, HIV-infected patients are at increased risk of postoperative infections due to compromised immune function. They are more prone to SSIs, with a significantly higher incidence compared to non-HIV-infected patients. For instance, Zhang et al. reported SSI rate of 47.5% in HIV-infected patients, compared to an average rate of 2.61% in the general population, particularly when preoperative CD4 counts were below 200 cells/╬╝L [4]. These patients also face an increased risk of developing postoperative sepsis, especially with low CD4 counts (below 100 cells/╬╝L), hypoalbuminemia, and when undergoing major surgical procedures [12,13].

Studies indicate that HIV-infected patients have a higher incidence of sinusitis, ranging from 41% to 71% [14]. This susceptibility is largely due to the gradual depletion of helper T cells, resulting in compromised humoral and cellular immunity, thereby making these patients more vulnerable to bacterial, viral, and fungal infections [15]. Delayed mucociliary transport has also been observed in HIV-infected individuals, leading to poor sinus drainage and an increased likelihood of developing sinusitis. The exact mechanism of this delay remains unclear, but may be related to the overall compromised immune status of these patients [15]. Chronic and recurrent sinusitis is common in individuals with low CD4 counts, with symptoms such as fever, headache, facial pain, and purulent nasal discharge. Opportunistic pathogens, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Aspergillus, and Mycobacterium avium, become more prevalent as CD4 counts drop below 50 cells/╬╝L [15].

HIV infection is not an absolute contraindication for dental treatment, but it can negatively impact treatment outcomes [10]. HIV-infected patients are at an increased risk for not only the above-mentioned postoperative inflammation but also various periodontal diseases and tooth loss [5-7]. Although Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) has reduced the severity and prevalence of HIV-associated periodontal diseases and tooth loss compared to those who are HIV-negative, HIV-infected patients remain susceptible to more severe forms of periodontal destruction, such as necrotizing periodontitis. Additionally, xerostomia induced by HAART and other HIV-associated conditions may increase caries risk, indirectly affecting long-term dental health [6,7].

From the author's perspective, there are several challenges associated with providing dental care to HIV-infected patients in general dental clinics. The primary concern for dentists treating HIV-infected patients is often the prevention of cross-infection, while the potential for increased treatment failure tends to be overlooked. Although the percentage of stigma and discrimination against HIV-infected patients in dental settings is relatively low, many patients choose not to disclose their serodiagnosis out of fear of being rejected [16]. This situation not only poses a hazard to dental professionals, but also endangers the health of HIV-infected patients themselves, as dentists cannot provide appropriate clinical and pharmaceutical care without full medical disclosure [16]. Moreover, conducting a comprehensive medical assessment prior to dental treatment in outpatient-based dental settings in Korea remains a significant challenge, as it is not yet a standard practice within the dental profession. Consequently, if a patient conceals their medical history or is unaware of it, the risk of negative treatment outcomes increases, along with the potential for infection or cross-infection among healthcare providers and other patients within the clinical setting [5-7].

Therefore, preoperative screening for HIV and other infectious diseases in dental clinics is crucial for planning appropriate treatment, including the preparation of personal protective equipment, antibiotic prophylaxis, and other preventive measures. This approach also helps to reduce the risk of postoperative complications, such as wound infections and delayed healing, while ensuring the safety of healthcare providers [5-7].

In conclusion, when providing dental treatment to AIDS patients in outpatient settings, it is essential not only to adhere strictly to sterilization and protective protocols to prevent infection, but also to recognize the increased risk of treatment failure and complications. To minimize these risks, it is crucial to consider appropriate HIV management and avoid overly aggressive treatment plans. The use of antibiotics before and after surgery should also be actively considered as a preventive measure. Furthermore, there is a need for a shift in perception regarding preoperative evaluations, even for dental procedures conducted under local anesthesia in outpatient-based dental clinics in Korea. Such assessments are vital to ensuring the safety of both patients and healthcare providers, as well as to achieving favorable treatment outcomes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the staff at Wonkwang University Sanbon Dental Hospital for their unwavering dedication and hard work, even in a clinical envi[1]ronment filled with numerous challenges and risks.

Figure┬Ā1.

Clinical and radiological findings at the patient's first visit and first operation. a. Panoramic radiograph at the first visit showing a mal-positioned implant fixture and alveolar bone perforation. b. Computed tomography at the first visit demonstrating a large alveolar bone perforation and inflamed sinus mucosa. c. Intraoral photograph at the first visit revealing an oroantral fistula. d. Inflamed sinus mucosa observed through the extended alveolar bone perforation after raising the gingival flap to manage the sinusitis and close the fistula.

Figure┬Ā2.

Clinical and radiological findings at follow-up and during sinus floor augmentation (SFA). a, b. Computed tomography (CT) and panoramic radiograph after treatment of prior sinusitis, showing a fully healed maxillary sinus with an alveolar bone defect. c. Clinical photograph before the SFA procedure, showing well-healed oral mucosa. d. Clinical photograph during the SFA procedure, showing a large bone perforation and regenerated sinus mucosa (white dotted line). e. Sinus mucosa elevated without tearing, and bone graft performed. f. Panoramic radiograph after SFA, showing well-positioned bone graft materials without scattering. g. CT taken after SFA. The air-fluid level suggests minor tearing of the sinus mucosa or congestion of blood/tissue fluid during membrane elevation. h. One-month postoperative follow-up CT showing near complete haziness in the operated maxillary sinus.

REFERENCES

1. Moreno Vazquez JC, Gonzalez de Rivera AS, Gil HS, Mifsut RS. Complication rate in 200 consecutive sinus lift procedures: guidelines for prevention and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014;72:892ŌĆō901.

2. Chirila L, Rotaru C, Filipov I, Sandulescu M. Management of acute maxillary sinusitis after sinus bone grafting procedures with simultaneous dental implants placement - a retrospective study. BMC Infect Dis 2016;16 Suppl 1:94.

3. Nolan PJ, Freeman K, Kraut RA. Correlation between Schneiderian membrane perforation and sinus lift graft outcome: a retrospective evaluation of 359 augmented sinus. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2014;72:47ŌĆō52.

4. Zhang L, Liu BC, Zhang XY, Li L, Xia XJ, Guo RZ. Prevention and treatment of surgical site infection in HIV-infected patients. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:115.

6. Holmstrup P, Westergaard J. HIV infection and periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 1998;18:37ŌĆō46.

7. Engeland CG, Jang P, Alves M, Marucha PT, Califano J. HIV infection and tooth loss. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2008;105:321ŌĆō6.

8. Nam JW. Efficacy of hydroxyapatite and fibrin sealant as carriers for bone morphogenetic protein-2 in maxillary sinus floor augmentation: a retrospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2024;53:795-801.

9. Halligan KP, Halligan TJ, Jeske AH, Koh SH. HIV: medical milestones and clinical challenges. Dent Clin North Am 2009;53:311ŌĆō22.

10. Nasi M, De Biasi S, Gibellini L, Bianchini E, Pecorini S, Bacca V et al. Ageing and inflammation in patients with HIV infection. Clin Exp Immunol 2017;187:44ŌĆō52.

11. Lv T, Cao W, Li T. HIV-related immune activation and inflammation: Current understanding and strategies. J Immunol Res 2021;2021:7316456.

12. Su J, Tsun A, Zhang L, Xia X, Li B, Guo R et al. Preoperative risk factors influencing the incidence of postoperative sepsis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: A retrospective cohort study. World J Surg 2013;37:774ŌĆō9.

13. Feng T, Feng X, Jiang C, Huang C, Liu B. Sepsis risk factors associated with HIV-1 patients undergoing surgery. Emerg Microbes Infect 2015;4:e59.

14. Del Borgo C, Del Forno A, Ottaviani F, Fantoni M. Sinusitis in HIV-infected patients. J Chemother 1997;9:83ŌĆō8.

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 0 Scopus

- 436 View

- 13 Download

- ORCID iDs

-

Jung-Woo Nam

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3445-5690 - Related articles

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print