Intraosseous hibernoma of the mandible: A case report

Article information

Abstract

Hibernoma is a benign tumor of brown adipose tissue, and intraosseous involvement is exceedingly uncommon. We report a 52-year-old man with a mandibular lesion incidentally detected on panoramic imaging. Panoramic radiograph showed a well-circumscribed radiolucency; cone-beam CT demonstrated internal calcified foci, cor-tical thinning, and adjacent sclerosis. The working differential favored non-ossifying fibroma and, less likely, a simple bone cyst. The lesion was treated by surgical enucleation with the extraction of the impacted third molar. Histopathology revealed large polygonal brown adipocytes with eosinophilic, multivacuolated cytoplasm, estab-lishing intraosseous hibernoma. At seven-month follow-up, radiographs showed internal osseous regeneration without recurrence. Initial differential diagnosis favored common mandibular lesions. The diagnosis of intraos-seous hibernoma was subsequently established by histopathology, underscoring the importance of radiologic–pathologic correlation in radiolucent jaw lesions with adjacent sclerotic features.

Introduction

Hibernoma is a rare benign soft tissue tumor composed of varying proportions of brown adipose cells originating from fetal tissue residue mixed with white adipose tissue. The name comes from its similarity to the brown fat of hibernating mammals. Hibernomas account for approximately 1.6% of all benign lipomatous tumors [1]. The exact etiology of hibernoma remains unknown. It typically occurs in individuals in the third to fifth decade of life, with a mean age of 38 years [1-3]. The tumor most commonly arises in the soft tissue of the thigh, shoulder, back, and neck, in regions where brown fat persists from fetal development into adulthood [2,3]. Hibernomas are usually slow-growing and asymptomatic. However, they can occasionally produce symptoms through compression of adjacent structures [1-4].

Intraosseous hibernoma is exceedingly rare and its radiographic features have only recently been described in the literature. Reported cases include those arising in the vertebral body, ischiopubic ramus, and iliac crest [5-9]. Herein, we present an additional case of intraosseous hibernoma within the mandible, together with a review of the clinical, radiographic, and pathological features of this rare entity.

Case Report

A 52-year-old male was referred to the Gangneung-Wonju National University Dental Hospital, from a local dental clinic for evaluation of a lesion in the left mandibular angle and ramus. The lesion had been identified on a panoramic image obtained for the extraction of the left mandibular second molar, five days prior to presenting to our hospital. Clinical examination, including both intraoral and extraoral assessments, revealed no remarkable findings.

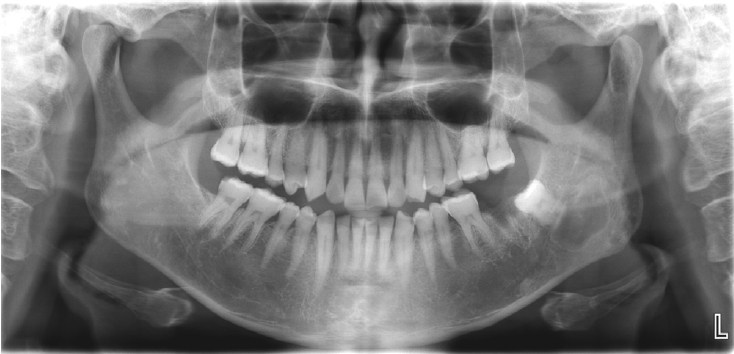

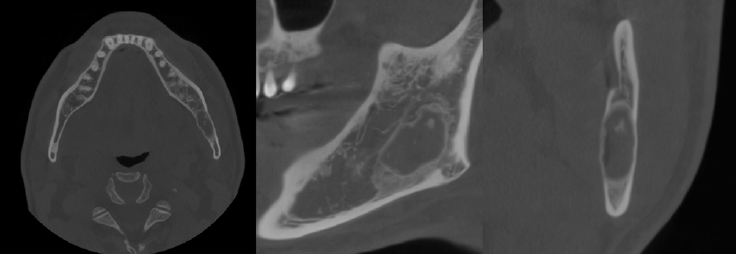

The patient underwent a panoramic radiograph and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT). The panoramic radiograph showed an ovoid, well-demarcated radiolucency with irregular contour, and internal lytic change beneath the periapical area of the left mandibular third molar region (Fig. 1). CBCT demonstrated a radiolucent lesion with a well-corticated margin and subtle internal calcified foci. Generalized sclerotic changes in the adjacent cancellous bone and thinning of the bucco-lingual cortex were noted, with mild expansion of the lingual cortex due to the lesion (Fig. 2). Anatomically, the lesion lay inferior to the mandibular canal and outside the tooth-bearing alveolus, which argued against an odontogenic origin. Collectively, these features were interpreted as a radiolucent lesion with surrounding sclerosis. Routine laboratory tests (L30 clinical chemistry panel) revealed elevated glucose (135 mg/dL) and total cholesterol (233 mg/dL), while all other parameters were within normal limits. Based on the clinical and radiographic findings-posterior mandibular location, well-defined unilocular radiolucency with a pronounced adjacent sclerotic change, cortical thinning with mild expansion but without periosteal reaction or cortical breach, and non-odontogenic position—the working differential favored non-ossifying fibroma, with a simple bone cyst considered less likely.

Panoramic radiograph shows a radiolucent lesion of irregular shape and relatively well-defined margins beneath the periapical area of the left mandibular third molar.

Axial, parapanoramic, and cross-sectional cone-beam computed tomographic images show a radiolucent lesion with a well-corticated margin and subtle internal calcified foci. Generalized sclerotic changes in the adjacent cancellous bone and thinning of the buccolingual cortex are noted, with mild expansion of the lingual cortex due to the lesion.

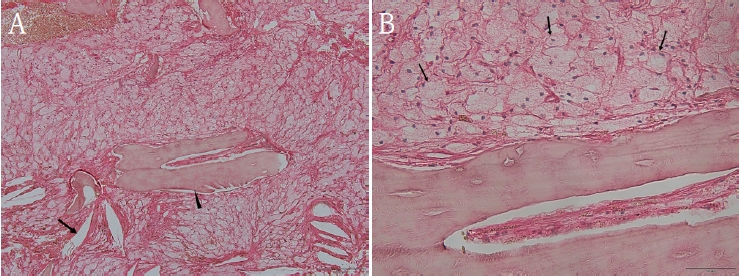

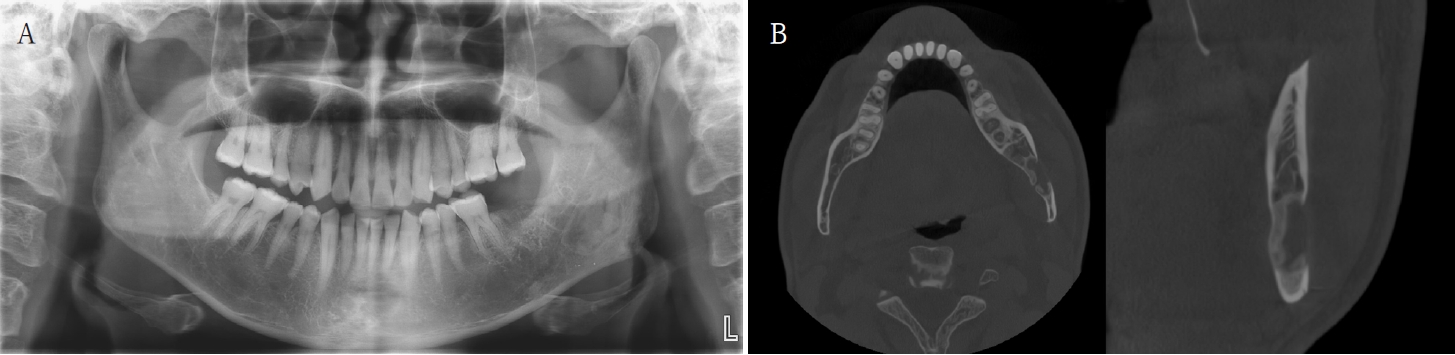

Histopathological analysis of the decalcified mandibular specimen revealed a mass predominantly composed of brown fat cells. Within the lesion, focal areas of cholesteatoma-like formation and numerous variably sized bony particle deposits were identified. Tumor cells exhibited eosinophilic granular cytoplasm with eccentric nuclei, consistent with adipocytic differentiation. Notably, the majority of the mass consisted of polygonal brown fat cells displaying multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles (Fig. 3). Based on the imaging appearance, the differential diagnosis favored non-ossifying fibroma, with simple bone cyst considered less likely. Intraosseous hibernoma was not initially suspected and was confirmed postoperatively by histopathologic examination. Overall, the findings supported a diagnosis of a lesion with extensive brown fat cells proliferation and secondary changes including bony particle deposition and cholesteatoma-like formation. These findings established the final diagnosis of intraosseous hibernoma. The patient has been followed periodically, and a 7-month postoperative panoramic radiograph and CBCT showed new bone formation along the superior, inferior, and lingual aspects of the postoperative defect consistent with healing, without evidence of recurrence (Fig. 4).

A. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E)–stained photomicrograph of the biopsy specimen shows large, polygonal brown fat cells with multiple cytoplasmic vacuoles, occasional cholesteatoma formation (arrow), and deposits of variably sized bony particles (arrowhead). B. H&E–stained photomicrograph of the biopsy specimen shows large, polygonal brown fat cells (arrow) have eosinophilic granular cytoplasm with eccentric nuclei (A. ×100; B. ×400).

A. Panoramic radiograph at 7 months postoperatively shows new bone formation along the superior and inferior aspects of the postoperative defect, without recurrence. B. Cone-beam computed tomographic images at 7 months shows new bone formation along the superior, inferior, and lingual aspects of the postoperative defect.

Discussion

Hibernoma is a rare benign soft-tissue tumor arising from brown fat. The majority of tumors occur in soft tissue of the thigh, trunk, upper extremity, neck, and abdomen. There is a slight male predilection, and most patients are middle-aged, with an average age of 38 years [2]. The predominant clinical finding is the presence of a slowly enlarging, painless mass. In comparison with soft tissue hibernoma, intraosseous hibernoma is extremely rare: however, it is increasingly recognized in recent literature [5]. Most cases arise in the axial skeleton-including the vertebral body, iliac crest, ischiopubic ramus, and sacrum-and are usually asymptomatic, being discovered during imaging studies.

The published cases share several imaging characteristics of intraosseous hibernoma. In prior studies, plain radiographs were seldom obtained, likely because these lesions predominate in the axial skeleton, where the superimposition of surrounding structures makes detection difficult [9]. CT scans typically reveal sclerotic or mixed sclerotic–lytic lesions with well-corticated margins, sometimes with a more pronounced sclerotic rim, and they may be accompanied by trabecular thickening [5-8]. Radiographic features of osteolysis in intraosseous hibernoma have been described only in a small minority of cases in CT scans [5,6].

MRI findings of intraosseous hibernoma are similar to those of soft tissue hibernoma, typically showing intermediate-to-low T1 signal, T2 hyperintensity, and variable enhancement, including peripheral rim, heterogeneous, or moderate diffuse enhancement. Reflecting brown fat’s mixed composition - lower lipid content with an increased cytoplasmic fraction - the T1 signal is lower than that of fat, whereas the T2 signal is relatively higher [6-9]. On short T1 inversion recovery (STIR), lesions usually show heterogeneous hyperintensity with effective fat suppression, consistent with this mixed fatty/vascular composition [8]. PET and bone scans often show mildly increased 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose uptake, reflecting the mitochondria-rich cytoplasm and their glucose hypermetabolism of brown fat [6,7,9,10].

Histopathologically, intraosseous hibernomas replace normal marrow with brown adipocytic neoplasm composed of brown fat cells with eosinophilic, granular or multivacuolated cytoplasm and centrally to eccentrically placed nuclei [1,2,5-9]. Furlong et al. reviewed 170 cases and emphasized the importance of recognizing its histopathologic spectrum to avoid misdiagnosis as other benign or malignant adipocytic tumors [2]. They also recognized several histologic variants, such as typical, myxoid, lipoma-like, and spindle cell type, based on the staining characteristics of cells, the nature of the stroma, and the presence of a spindle cell component. Immunohistochemical studies confirm positivity for S100 and adipophilin, helping to differentiate intraosseous hibernomas from mimicking entities such as liposarcoma, foamy histiocytes, or notochordal lesions [5-7]. Nord et al. demonstrated that concomitant deletions of the tumor suppressor genes MEN1 and AIP in hibernomas, with increased expression of brown-fat–associated genes such as UCP1 and PPARG [11].

The differential diagnosis of solitary sclerotic bone lesions remains challenging because intraosseous hibernomas mimic multiple entities. Benign notochordal cell tumors usually occur in the midline, show sclerotic changes on CT, T1-weighted hypointensity, and lack of enhancement on MRI. Atypical hemangiomas may resemble intraosseous hibernomas due to T1-weighted hypointensity and T2-weighted hyperintensity; however, they typically display lower T1-weighted signals related to increased vascularity and sclerosis, with heterogeneous enhancement. Metastatic lesions also present overlapping features, often with lower signal intensity than intervertebral discs [5-7]. Although PET can be supportive, definitive diagnosis requires biopsy and histopathologic confirmation. Clinically, most intraosseous hibernomas require no treatment; however, complete excision may be performed for symptomatic or diagnostically indeterminate cases. The prognosis is excellent, and recurrence has not been reported following complete resection [5-7].

In our case, an intraosseous mandibular lesion was incidentally identified as a radiolucent defect with surrounding sclerosis and internal lytic change on panoramic radiograph and CBCT. At the time of presentation, the working diagnosis favored non-ossifying fibroma; accordingly, we did not pursue additional cross-sectional imaging such as contrast-enhanced CT or MRI beyond the CBCT already obtained. We acknowledge the inherent limitations of this imaging work-up; however, the observed combination of a well-corticated radiolucency, surrounding sclerosis, and focal internal lysis is concordant with CT features described in prior studies of intraosseous lesions [5-9]. Although immunohistochemical studies were not documented, the histopathologic findings-multivacuolated brown fat cells with central-to-eccentric nuclei, deposition of variably sized bony particles-were in keeping with prior descriptions. While immunohistochemistry can support the diagnosis of intraosseous hibernoma, the limited availability of tissue for ancillary testing is acknowledged as a limitation; however, immunohistochemical studies would not have altered the diagnosis or management.

We consider our case to represent the eosinophilic-cell subtype of hibernoma, as classified by Furlong et al., given that white fat cells were observed only rarely on histopathologic examination [2]. In addition, preservation of the bony trabeculae in our specimen aligns with the observation by Song et al [7]. However, the focal cholesteatoma-like formation identified within the lesion appears to be an incidental finding and, to our knowledge, has not been previously reported, particularly in intraosseous hibernoma.

A cautious explanation is that this lesion may have arisen from residual fetal brown fat cells that persist into adulthood and subsequently developed subtle dysregulation of normal control. This could allow limited local expansion of brown fat cells without malignant behavior. However, this remains a speculative hypothesis and would require supportive molecular studies to be confirmed.

The final diagnosis in our patient was therefore established by histopathologic examination, in keeping with current practice when imaging findings are suggestive but not pathognomonic. Although limited by the single-case nature and relatively short follow-up period, this report expands the anatomic spectrum of intraosseous hibernoma to include the mandible. When radiolucent mandibular lesions with mixed sclerotic features are encountered, intraosseous hibernoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Careful correlation of radiologic and pathologic findings, coupled with long-term observation, is critical for accurate diagnosis and optimal management.

Notes

Conflicts of Interest

None